← Archive home

Town Planner Fiona Sibley argues we should be paying more attention to the social outcomes of development.

What does a fair city look like? A fairer city should look to reduce socio-economic inequalities, and stimulate a lasting, upward trajectory for residents, workers and occupants to achieve their aspirations and thrive, regardless of background or circumstances. The concept of fairness is linked to equality and inclusion, which are in large part influenced by affordability. How equitable is the distribution of jobs, housing and community facilities, and the infrastructure that connects them? How can buildings and places actively promote social cohesion and equal opportunities? These are questions that every project should consider from the outset.

As urbanists and designers of cities, we are increasingly approached to develop placemaking strategies that will deliver a stronger social fabric. These might consider the integration of features that promote inclusivity, wellbeing, belonging and community success, alongside social value strategies that offer outreach from our professions into those communities, and welcome apprenticeships into our studios.

“Cities are often viewed as engines of economic activity, but they are also shapers of community.”

Can city design influence this agenda? Of course. We all know of examples where the built environment doesn’t play fair – communities segregated by housing tenure, ‘poor doors’, playgrounds accessible only to private residents, luxury apartments with nil affordable housing provision justified on viability grounds, neighbourhoods with food poverty and lack of access to quality education, perpetuating social inequality. Even the most economically successful and environmentally progressive cities are failing if they only serve the needs of limited sectors of the population. Lack of affordability in cities like London and New York is an obvious example of unfairness that generates hardship and exclusion. Cities are often viewed as engines of economic activity, but they are also shapers of community, and significant determinants of the socio-economic outcomes of their inhabitants. Design and development strategy can be key to driving the pursuit of fairness, at every level.

Social value – the tangible output generated in addition to commercial value – increasingly drives commercial decision-making. In a built environment context, this means that development must not purely drive financial gains for its developers, but demonstrate tangible benefits for the communities as well. Investors are now applying non-financial Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors to their investment decisions, and companies are pursuing B Corp certification, which demonstrates a high social and environmental performance.

Our work for Grosvenor on a new community of 5,000 homes in Essex is being planned with our client’s Community Charter in mind. This document outlines Grosvenor’s commitment to delivering development in collaboration with communities, seeking outcomes that put people’s interests at heart. As town planners, our research for the development strategy has centred around the guiding concept of social mobility. This has led us to consider how we can influence social mobility in two ways; by designing out aspects of the physical environment that can exacerbate inequality, and secondly, by facilitating levels of service provision that offer the vital lifelines a community needs, that will in turn widen opportunity.

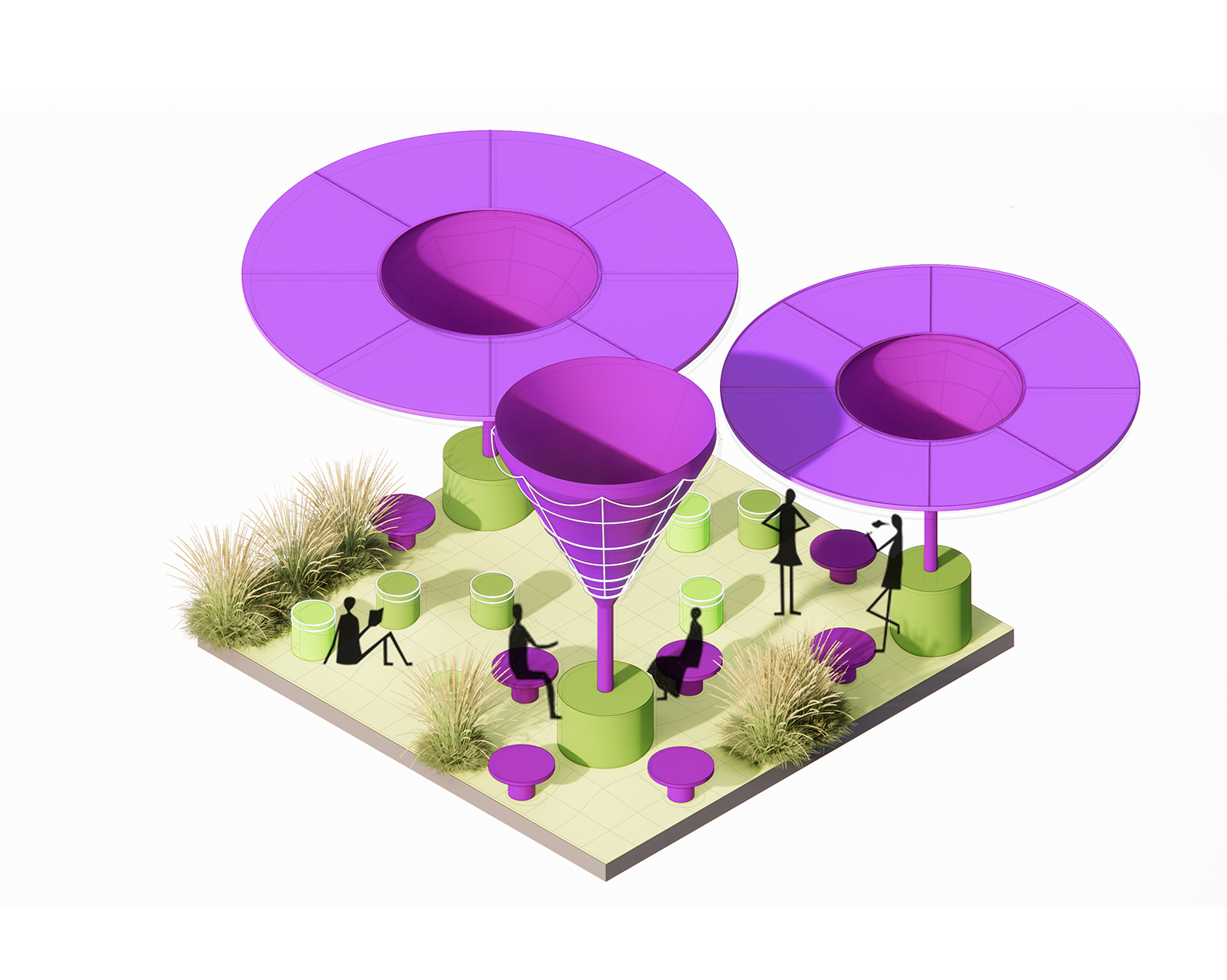

How we establish and articulate those specific needs before applying solutions is important. This is where community engagement, governance and participatory planning comes to the fore. For example, teenage girls are much less comfortable users of public spaces than boys – a statistic highlighted by the Make Space for Girls Foundation. Through active engagement with young people, we learn what they want – girls prefer swings where they can face each other to chat, not sports pitches which suggest competitiveness. Diversity in our profession means diversity in our proposals: we are stronger as a profession when we display a more empathic understanding of the breadth of user experiences. Our Toronto studio’s Reina Condos, designed by women, for women, has features that might not have been conceived by a different design team, or a less progressive brief.

So how can we use these ideas to change the way people experience the cities they inhabit? What does change look like, and what constitutes success? A socially-led development agenda balances flexibility and proximity between work and home, how affordable childcare can free up time for care-givers to play a more active role in community life, and how the location of specialist housing for older people can engender inter-generational connections and combat loneliness. We are working on ways to design neighbourhoods differently, bringing these ideas to the forefront. Such strategies can engender a greater sense of belonging, empowering people to achieve the lives they want to lead; whether focused around the school gates, hobbies, volunteering, looking out for neighbours or simply having more time for self-care and nurturing wellbeing. Social interaction has proven benefits for mental health. Measures of success and evidence are important to ground ambitions around fairer cities in reality. Strategies need to be measurable, achievable, and in the best instances subject to evaluation, so we can learn from what works best, and not stand accused of making trite promises to people and communities. We achieve that by defining specific KPIs at the outset that establish what success looks like, which are then used to measure the results.

Design in the 21st century needs to address this question: how do we redress the balance and make our cities fairer? BDP’s history and ethos makes us well placed to lead this charge. By pushing for this agenda, we would like to see fairness articulated as a top sustainability priority. We must continue to challenge our clients to advance EDI through their briefs, and strive for positive social impact.

People want to feel a sense of belonging and to know that their needs are understood and met. That’s the singular objective we need to pursue to make our cities truly fair.